I first stumbled across the concept of crowdsourcing a few years ago, when a small globe symbol appeared in the bottom right hand corner of my Facebook profile. Intrigued, I followed the link to Facebook Translate, an application that enables any user to contribute their own translations of the ever-expanding site content. In an impressive feat of translation ‘by the crowd’, Facebook was translated into French in a 24 hour period by a group of 4000 volunteers in 2008. But what implications does this open call principle have for the translation industry?

The term ‘crowdsourcing’ was coined by technology writer Jeff Howe in 2006 to refer to the outsourcing of tasks to a large, undefined group of people. Just as people now tend to turn to Wikipedia rather than the Encyclopaedia Britannica, or to Twitter in place of a newspaper or the radio, organisations are now employing similar social, collaborative tactics to fulfil their growing translation needs.

Crowdsourced translation involves gathering large groups of volunteers to collectively translate content, most commonly by means of an online translation platform, for little or no payment. The rise of user-generated content and an increasingly participatory internet culture mean that web users are now accustomed to contributing as well as merely consuming, with these changing habits going hand in hand with crowdsourcing principles.

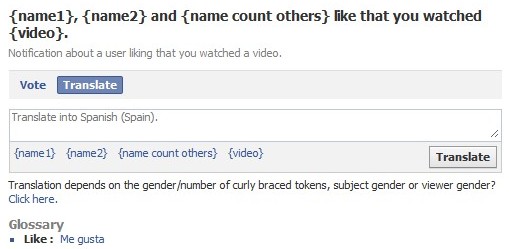

Crowdsourcing could be considered a natural progression from the fansubbing of videos and games and mass fan translation of novels, as has been seen working to great effect on numerous projects including the fan translation of Harry Potter into Chinese by 60 volunteers in 2007. Crowdsourcing has taken the process a step further by incorporating sophisticated translation platforms, translator ranking systems and quality control stages similar to those in a typical translation workflow. Facebook Translate, for example, provides users with a style guide, glossary suggestions and facilities to copy in previously translated content, mimicking many of the features of a traditional CAT tool.

The Facebook Translate Application

Quality control is carried out by other members of the crowd, who are able to vote on and modify the translations, with the aim of weeding out poor, inaccurate or prank translations. Crowdsourcing has been used successfully in this way for translating sites with large amounts of rapidly changing, dynamic content, as well as not-for-profit organisations like Kiva, which rely on large groups of voluntary translators to provide pro bono translations. Generally speaking, it is most successful in situations where speed and accessibility take precedence over quality and accuracy. It can also serve to boost the presence of minority languages online and allow speakers of these languages to take translation needs into their own hands, proud of the knowledge that this will benefit their fellow language community.

One growing trend to keep an eye will be the merging of machine translation with crowdsourced translation, putting content through machine translation software before asking the anonymous ‘crowd’ to approve or modify these translations (as we discussed in an earlier blog here). This has sparked fears and protest from some that the role of a professional translator is being undermined and will soon be reduced to that of post-editor, although in the long-term it seems unlikely that many specialist text types typically associated with professional translation could ever be freely dished out to the crowd.

But what threat does this trend really pose to professional translators, and to the industry as a whole? And what is it that motivates a web user to become part of this free translation workforce? Look out for more on this in the coming weeks.

12 November 2013 16:43